Dear avid readers of the Jaffe Family Newsletter,

Welcome to the penultimate edition of the Jaffe Family Book Club on Jacqueline Susann’s 1966 satirical masterpiece VALLEY OF THE DOLLS. This is an exchange of letters between John and BB on genre, the representation of men in the novel, and whether the Susann’s representation of show business is “turgid.” John thinks so, BB thinks not. Why? Read and see!

B,

Tragedy or satire? Hmm. Some of both, I’d say. But it’s a complicated recipe and, in it, I’d mix some other ingredients.

Social observation — Susann is certainly using exaggeration to expose bad stuff, which is standard satire. But I think she’s also holding up a mirror to the 1950s-‘60s and saying, “Look, this is what we’re becoming.” And some of the deliciousness of VOD is that, underneath the over-the-top, she’s actually approving of what we’re becoming. The role and power of women, for example. Clearly, she thinks much of a woman’s power is based on some kind of fundamental, neolithic sexual strategy. But inserted occasionally is the idea that women have intrinsic worth beyond what the patrimony is willing to allow. Here’s a great quote from Anne:

“My identity, maybe my future, my whole life. Giving up before it begins. Neely, nothing ever happened to anyone in my family. They married, had children, and that was it. I want things to happen to me. I want to feel things, to—”

Notice how you could put this into the mouth of a male character and it would work just as well. In fact, I think she kinda does this with

Lyon. Here’s another:

"The office was filled with the activity of the Ed Holson radio show. But Anne was exhilarated with all the excitement around her. She was busy with her work; Henry needed her; Helen and Neely needed her; she was climbing Mount Everest and the air was invigorating and wonderful. Even if every second verged on crisis, this was part of living—not just watching from the sidelines.”

Not just watching from the sidelines. All the women characters are doers, not watchers. Including Susann, when she wrote this book. Of course all the women needed special help to achieve things, unlike the men. I don’t recall any of the men taking “dolls.” Does this mean that deep-down men are stronger, better? Well, that’s one of the great questions of the book. Ultimately, did Susann make women look weaker? Trading their place in the patrimony for a place in pharmacology?

Exploitation — Let’s face it. Susann threw in everything she could think of to grab the great publicity machine (the same machine she so shamelessly shames in the book) and make VOD a smash. Sex, drugs, movies, sex, stage, TV, sex, infidelity, insanity, inebriation. And did I mention sex? The country was getting deep into the idea of the “Sixties,” when VOD came out. You have to understand what changes that decade brought in societal norms. The No. 1 Billboard hit of 1960 was “Theme from a Summer Place” by Percy Faith (give it a listen). 1969 was the year of Woodstock. “Abby Road” was the top album of 1970. Did Susann have some underlying noble themes? Sure. Did she want to jump on the Sixties bandwagon of "sex, drugs and rock and roll”? Oh, yeah. VOD couldn’t, even then, be considered pornographic (though it would have 10 years before) but she loved to titillate. In 1966 this would have been, let’s say “risqué.”

“Uh huh. It hurt a lot and I didn’t come. But Mel made me come the other way.”

“What are you talking about”

”He went down on me."

Sixties — Speaking of the greatest decade. . .Though the book pretends to extend from the mid-1940s to the ‘60s. All the tropes are about her present day. She hardly pretends to look back. For example, at one point early on in the narrative (1946 or 1947) she has Jennifer complain to Anne: “You’ve worn out that album.” Sorry, Susann, albums weren’t even invented until 1948. This was a complaint people made from the mid-1950s to the ‘80s (when CDs were invented). And she seems to make a concerted effort to avoid the political, international, broad societal upheavals going on all around her characters. Everything from civil rights to war (cold and hot) to men landing on the moon happened in the Sixties. She sticks to the war between the sexes and show biz. And her show biz stuff is a little turgid. Consider that, just a couple of years after this book appeared, “I am Curious Yellow,” a high-falutin’ porn film from Sweden, was No. 1 one at the U.S. box office in November 1969.

But I could go on and on.. . . .

BB’s response:

Dear John,

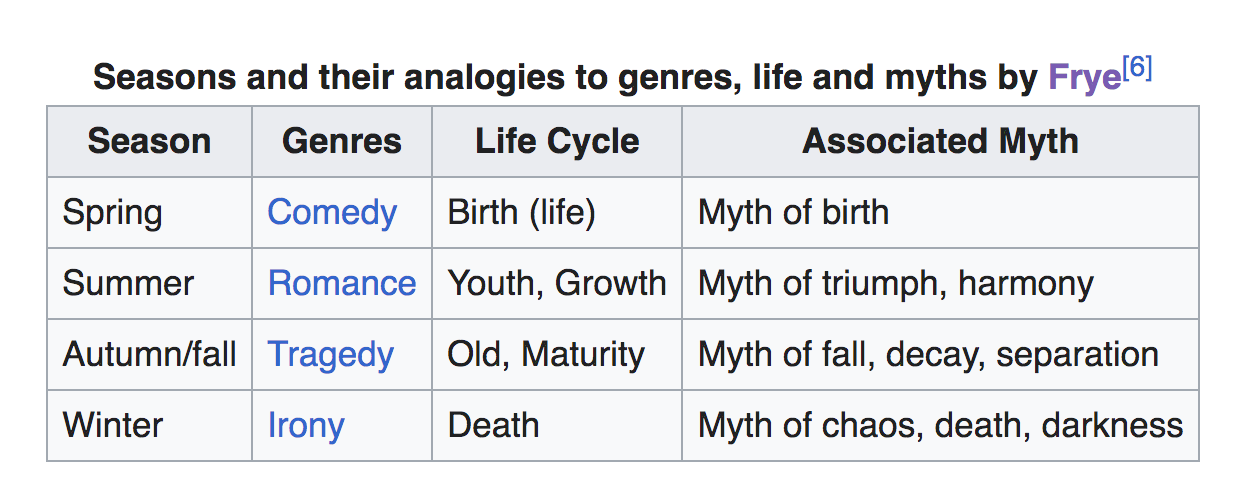

Thank you for giving me an opportunity to talk about Northrop Frye. This will be more of a pan Frye than a deep Frye because there’s much else to write about. Still I hope this lures you or some reader into the pleasures of Fryethought. Frye was a Canadian literary scholar, 1912-1991, a professor (and chancellor) at the University of Toronto and frenemy of Marshall McLuhan. Frye’s masterwork is the 1957 “Anatomy of Criticism.” With this book Northrop sought to ground literary criticism like, say, Newton grounded physics with the Principia Mathematica or Darwin biology with the Origin of Species. I’m not sure how long it took for Newton to become axiomatic to physics, but with Darwin, the process took decades, maybe nearly a century. Therefore it isn’t too late for Frye’s wonderful book to inspire an actual science of literature, as opposed to what literary criticism is mostly now - imaginary politics pursued with the literary text as prop/victim.

What does The Anatomy of Criticism have to do with the Valley of the Dolls? Frye proposes an analogy between seasons and genres: Spring and comedy go together, epic and summer, tragedy and fall, and satire and winter. What’s the different between tragedy and satire?

Tragedies are, to quote that helpful wikipedia diagram, “myths of fall, decay, and separation”. Satires are “chaos, death, darkness.” But Valley of the Dolls is (as you say) both: a myth of fall, decay, separation, chaos, decay, death and darkness.

But is it really the story of a fall? Are these noble people who decline? No, not really, they seem degraded from the beginning. There is very little dignity in this book: Ann is generous, perhaps, but relatively dim. Everyone else is some kind of monster, or, like Jennifer, a destined victim.

Jennifer’s story also lets me defend the book against your suggestion that Susann’s

“show biz stuff is a little turgid. Consider that, just a couple of years after this book appeared, “I am Curious Yellow,” a high-falutin’ porn film from Sweden, was No. 1 one at the U.S. box office in November 1969.”

John, first of all, we sophisticated people high-falutin porno “erotic cinema.” Second, Jennifer makes these kind of movies! That’s how she gets famous in the book! Susann anticipates the success of I Am Curious Yellow. Here’s a conversation between Jennifer and Claude, the director of the skin flicks. Claude speaks first:

“You are the sex goddess of Europe. All Hollywood is waiting to see how you measure up to their sex symbols—Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor—and those girls are young.”

“I’m not Liz Taylor or Marilyn Monroe. I’m Jennifer North. I’m me!”

“And what are you? A face and a pair of breasts! That’s all you are . . . all you’ve ever been!”

“I haven’t done a nude scene in my last seven pictures!”

“Because the image is planted. You could wear a burlap bag, but everyone knows what’s under it. They know every inch of your body by heart, and they see it no matter what you wear. Don’t ever get it into your head that you have anything else to offer.”

“Then the image exists in America, too. They’ve seen all my pictures.”

“Jennifer, don’t you trust my judgment?” His manner changed and he tried a gentle smile. “You do have something else. There are plenty of naked stars in Europe, but they cannot touch you. Because you have one extra ingredient. A sweetness, a youthful sweetness that no French girl seems to have. They can be piquant, mischievous, naive—but you have that American freshness. And that freshness can only be retained with youth. A young face. Despite the golden hair and the sexy breasts, there is something about your looks that conveys an impression of innocence, of girlishness . . . almost of purity. Now, we have no problems with your body. It’s still marvelous—but you’ve got to drop ten pounds.”

Retract your slanders!

Likewise: I do not think the men in this book are any stronger or better than the women. Harry is successful but extremely lonely, Lyon a philanderer and liar, Allen an entitled twit, his father, Gino, a cretinous cock on legs. Neely’s bisexual husband Paul is equally pitiful and dishonest, and her poor first husband is just another victim. Where are the strong men in the valley of the dolls? Do they take pills? Maybe drink, instead?

What about your thoughts about a sequel? What comes after the Valley of the Dolls? Maybe feminist time travelers from the future travel back to 1947 and give these three lost women the knowledge and tools they need to save themselves from drug addiction and destroy the patriarchy? It’s sure to be a hit.

As for our next book, I know you and Mom are reading the Inspector Montalbano novels, but let me advocate once again for THE LEOPARD. I don’t know of any book that GETS the strange vibe here, plus (to me, at least) it’s as magical and more perfect a novel than 100 years of solitude; less sprawling, with a peculiar, slice-of life narrative structure and one of the more disturbing endings of all known literature. Did I pump it enough? Are you ready to climb on THE LEOPARD?

With love,

BB